|

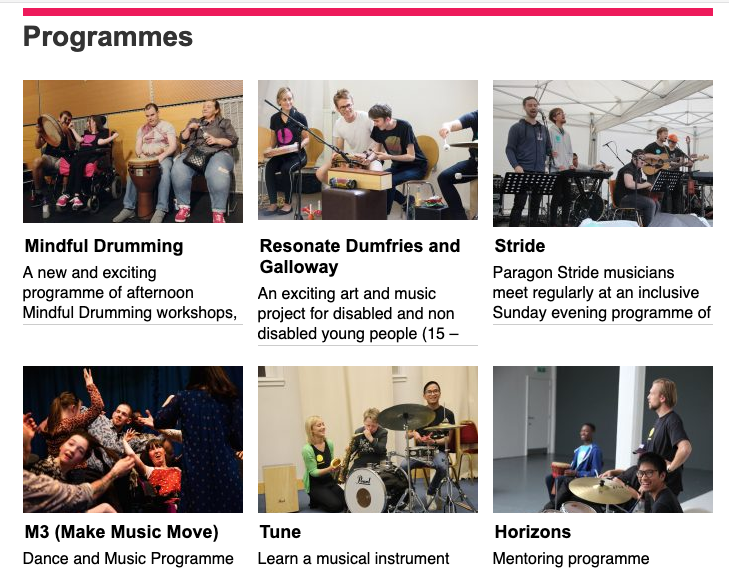

In my search for best practices in the areas of creativity and inclusion, I was fortunate enough to connect with Paragon Music, an organization whose mission is to use "music and the arts to raise peopleʼs aspirations, promoting positive self-image, teamwork, communication and learning." Little did I know that when I sat down with the dynamic team of this inspiring organization that they would spark a paradigm shift in my thinking about inclusive education. Instead of starting with a prescribed curriculum or repertoire in which young people who receive additional support needs must find ways to "fit in" by adjusting instrumentation or physical/cognitive complexity, Paragon Music always centers on the student by drawing out the interests, ideas and assets of each ensemble member to create original compositions. Here is a video that beautifully conveys the spirit, philosophy and teaching approaches of Paragon Music. Creative contribution from all participants forms the foundation of Paragonʼs inclusive pedagogy, which is very different from inclusive practice. According to McIntyre (2009), inclusive pedagogy is "a collaborative approach to teaching based on the idea that all children can learn together, and that participation in learning requires responses to individual differences among learners that do not depend on ability labeling or group, or the withdrawal of the learner for additional classroom support" (p. 603). Dr. Lio Moscardini who serves on the board of Paragon, is a lecturer at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Learning and Teaching in the Performing Arts and is internationally recognized for his work in inclusive education, kindly shared with me the important distinction between inclusive practice and inclusive pedagogy in the music classroom: While in Glasgow, I was able to volunteer for Paragonʼs Tune, which meets on Saturday afternoons and provides young people (6-16) with additional support needs opportunities to learn an instrument and create and perform music as an ensemble. It was here that I witnessed inclusive pedagogy in action. Every session begins with a community circle and creative warm-up followed by the ritualistic ending of "We Will Rock You." If a child is reluctant to join the circle, staff find ways to include them in purposeful and meaningful ways. For example, one young boy who preferred to walk the periphery of of the room, gladly accepted the job of signaling the start and end of the community circle by playing the triangle. No matter where he was in the room, this boy was keenly aware of the groupʼs activities and didnʼt miss his cue from the music instructor to ring the triangle. Students then moved into their first 45-minute session of either individual or group work. I was interested to learn more about the creative composition process for ensembles, so I focused most of my observations on these sessions. What I saw was creativity in all of its forms: teaching practice, process and performance. It is no wonder that Paragon won the 2015 Royal Bank of Scotland Community Project of the Year: Finding Scotland’s Real Heroes, which recognizes projects across Scotland that make a huge difference to the communities they serve. This video gives a snapshot of Paragonʼs Tune program:  Here are some observations from my first visit:

The social impact that Paragonʼs Tune program is evident in just a 2-hour visit. What I witnessed was validated by a social impact report prepared by the Social Value Lab in 2014. The evaluator noted these impacts while observing Paragonʼs Tune program:

This last bullet point is an important one: when focus is placed on a musicianʼs ability, rather than disability, the experience is asset-building and can be transformative for both teacher and student. Paragon removes labels, challenges assumptions and preconceptions and collaboratively works alongside young musicians to provide "expertly timed opportunistic interventions to catch the moment for participants where cognitive skill, creative skills, communication skills, self-presentation skills could be taken a step forward" (Social Value Lab, 2014, p. 8). With labels removed and opportunities increased, Paragon opens its participants to the process of "positive signification" or "resignification" (Mullen & Deane, 2018). According to Mullen and Deane (2018), "Negative labelling sets a self-fulfilling prophecy in motion, whereby people judge the behavior that accords with the label as typical of the individual, and the labelled individual comes to develop a self-image, which is in keeping with the label...By giving the participants support and validation in terms of their own musical identities…the young people involved positively transform their perceptions of both their musical and their wider selves” (p. 145). The teaching practices and philosophy behind Paragon Music address all areas of my research project: creativity, student identity and agency, and well-being. Iʼm excited to bring these practices into my music room back at Glacier Valley Elementary School in Juneau. Paragon Music is a gift to the Glasgow community and a forward-thinking model in the fields of music education, creativity and inclusion. They offer a host of different programs in music and dance for all walks of life with a wide range of additional support needs. Thank you, Nin, Charlotte, Lio, Fiona and the rest of this dedicated Paragon Music staff for welcoming me as a volunteer for Play-On and for providing inspiring teaching practices and experiences in inclusive pedagogy and creativity to take back to Juneau with me! References

McIntyre, D. (2009). The difficulties of inclusive pedagogy for initial teacher education and some thoughts on the way forward. Teaching and Teacher Education,25, 602e608. Mullen, P., & Deane, K. (2018). Strategic working with children and young people in challenging circumstances. The Oxford Handbook of Community Music, 177 Social Value Lab (2014). Social impact of the Paragon programmes: Report for Paragon.

3 Comments

This short film, narrated by Keir Bloomer, a member of the original Curriculum Review Group, explains the background to the Curriculum for Excellence. As part of my Fulbright tenure in Glasgow, I attended classes at the University of Strathclyde for music students pursuing a Professional Graduate Diploma in Education (PGDE). The Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) is the national curriculum for Scottish schools for students ages 3 to 18, which was developed in 2002. Since this document was the foundation of all of the coursework for the PGDE students, I did some digging into its origins and documents related to the Expressive Arts. The video above visually outlines the how and why of CfE. Iʼve summarized many of its points below: In 2002 a national debate about the role of education occurred in Scotland involving 25,000 people, mainly parents. Although most people felt that Scotlandʼs schools were doing a good job, they recognized that the world is changing dramatically so education also needs to change to meet the challenges of the 21st century. These challenges included:

To address these challenges, the Curriculum for Excellence was developed to help children and young people develop these four capacities (

The principle teacher of music and her students at Kingʼs Park Secondary School in Glasgow created this video to explain how the four capacities are developed in the music classroom: When designing lessons, educators of all disciplines should keep these seven principles in mind:

Below are links to documents particular to the Expressive Arts that address principles and practices, benchmarks and experiences, and outcomes. Keir Bloomer, a member of the original Curriculum Review Group, explained in the above video that "the Curriculum for Excellence is badly named. It is not a curriculum - at least if you envisage a curriculum to be a catalog of content - things to learn. Curriculum for Excellence is firstly a mission statement." He continues to explain that CfE is not something to be implemented just over several years, but rather guide education for decades to come. CfE is also a plan of improvement, interdisciplinary learning in a global context, and a new emphasis on learner engagement, where the student is actively involved in the learning process. In the Expressive Arts Principles and Practice document I was pleased to see this question and how it is addressed: How important is inspiration and enjoyment?

I appreciate a curriculum that recognizes the enjoyment and inspirational value of the arts as an important part of its outcomes and states it boldly in the first few pages of its document. CfE is not so prescribed, but has freedom and flexibility built-in for teachers as long as their practices are tied to the key principles and outcomes, and I observed this in the secondary music classrooms I visited in Glasgow these past 5 months. |

Lorrie HeagyThis is a personal blog, sharing my experiences living in the UK from January - June 2019 as a Fulbright Distinguished Award in Teaching scholar. This blog is not an official site of the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State. The views expressed on this site are entirely my own and do not represent the views of the Fulbright Program, the U.S. Department of State, or any of its partner organizations. Archives

July 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed