|

I attended a Make Music Day UK planning meeting at the Scottish Music Centre just down the street from the University of Strathclyde. According to their website, Make Music Day was launched in France June 21, 1982 as the Fête de la Musique. Held on the longest day of the year, "The Fête has turned into a true national holiday: France shuts down on the summer solstice and musicians take over. Almost 8% of the country (5 million people) have played an instrument or sung in public for the Fête de la Musique. Thirty years later, this free celebration is held in over 800 cities in 120 countries. Anyone can participate: amateur, professional, young and old. The only requirements are that the musical event must be free and open to the public. Glasgow was involved last year and plans to increase its numbers for this year. You can help your community launch/expand its Make Music events by utilizing the toolkits, videos and other resources housed on the main website. There is a Make Music Day anthem, Bring Me Sunshine, with downloadable parts for voice, orchestra, ukulele, guitar and piano.

The Make Music Day UK website encourages people to make music a regular part of their lives by checking out the Making Music UK website, which houses a searchable database of the thousands of amateur music groups across the UK. The UK themes include electronic music, libraries, Go Rural, Make Music Day Song, Do It Digitally and International Collaborations. The current list of participating cities, states and countries does not have Alaska on there - yet! What do you say, Juneau?

1 Comment

Living abroad for six months could be very isolating, especially when traveling alone. Fortunately music has created pockets of community wherever I go. In Glasgow, I have weekly mandolin and fiddle lessons at the Glasgow Folk Workshop where the customary tea and comfort break is built-in to the 2-hour lesson and allows me to not only mingle with my fellow classmates, but also make new friends. The fiddle weekend in Kelso, also opened me to the network of Fèis going on throughout the year, which often come in the form of extended weekends, holidays or summer camps. It took some digging online to find one or two of these gatherings, but once I attended one, I was dialed into an entire network often through word-of-mouth. Folks attending one Fèis tend to participate in others, so people generously share what they know. These fèisean are great ways to connect with people from all over the UK and reconnect with each other in the future. Fèis Gleann Albainn is one of those gatherings. It is held every March in the beautiful town of Fort Augustus, situated along the shores of Loch Ness (yes, the same Loch Ness monster fame). When I walked into my first fiddle class, I was impressed again by the caliber of teaching talent. One participant quietly gasped in awe of the folks assembled here to teach and inspire us. All of the tutors (pictured above) played in bands and taught extensively. These professional musicians help sustain and grow the number of people playing traditional Scottish music because of their teaching and inspiring performances. Check out their websites and consider supporting their music: Much like Kelso, we arrived Friday night to play a session where folks registered, reconnected, laughed, played and socialized over a drink. Saturday and Sunday were full days of teaching with just a 2-hour break before people gathered for an evening session in pubs throughout town based upon their playing level. Since I was a beginner at Scottish fiddling, I planted myself in the Slow Session held at the hostel where many people visited later to jam through the wee hours of the morning. Like Kelso, these sessions were highly motivational and inclusive. Every space was utilized for mini-jam sessions based upon skill or knowledge of pieces and all were welcome to join. Even though I didnʼt know many of the pieces, I felt much more comfortable learning by ear, especially during the day classes where I held my own - more quickly finding anchor notes, listening for patterns and intervals, and connecting all of this to the basic form of a traditional Scottish tune. Tutors also repeated passages many times over until the sound was more fluid and musical. I used each repetition to isolate a particular skill (i.e. bowing, fingering, staying relaxed, etc.)

When I returned to Glasgow and my GFW mandolin and fiddle lessons, I recognized many of the Fort Augustus faces in the crowd. Yes, music creates community and friendship! For those of you interested in Fèis being offered throughout the year for adults, hereʼs what I found:

I would like to thank FiddleClass.com for creating a list of fiddle classes throughout Scotland, which helped me locate my first Fèis, Leon Firth for his company at breakfast and the bus trip back to Glasgow and Bill Skeoch, for organizing a stellar weekend in Fort Augustus. While in London for the Inclusive Practice in Action workshop, I arrived a couple days early to meet with folks from the Creative Learning Department at Guildhall School of Music and Drama, visit the National Gallery and Portrait Gallery, explore the Churchill War Rooms and see a musical or two (or three). Although I wasnʼt able to meet with anyone from Guildhall, I did learn that the Paul Hamlyn Foundation commissioned Guildhall to develop a creative and collective Classroom Workshopping project as a FREE downloadable resource housed on the Musical Futures website. The website provides teacher notes, downloads and audio and video. In 11 short video clips, Guildhall teachers model the creative composition process with students from the Musical Futures Champion School, Morpeth School. Many of the Musical Futuresʼ resources are free to access. All you need to do is create a Musical Futures account - also free. The website has a wealth of resources and trainings for music teachers across the globe. Check them out! Here is the first of eleven short clips modeling the Classroom Workshopping project: The National Gallery and Portrait Gallery were incredible and overwhelming, but what Iʼd like to highlight is the Churchill War Rooms. I felt like I was traveling back in time, as many of the 20+ underground rooms were kept largely intact - including wartime wall maps, switchboard and telephones, and living quarters. As part of the ticket price, you get a portable audio tour, featuring interviews with key staff and Churchillʼs inspiring speeches. They also have a museum dedicated to Churchillʼs life. An extraordinary man who bolstered the morale and determination of the British people. This a must-stop for anyone visiting London. And finally, I treated myself to a couple of musicals (I am a music teacher afterall):

Jess Thon, co-founder of TourettesHero, opened the Inclusive Practice in Action workshop with an inspiring keynote on inclusion. This one day of workshops and discussions focused on the themes of Early Years, Youth Voice and Social Justice. TourettesHero celebrates the humor and spontaneous creativity that comes from someone with this condition. The mission of this organization is to change the world one tic at a time. Jess shared how her thinking around tourettes transformed when Matthew Pountney, the co-founder of TourettesHero, described her tourettes as a crazy language generating machine and not doing something with it would be wasteful. Jessʼ tics have inspired creative thinking and visual art because her tics often combine words or phrases that spark a new way of seeing things. Examples include: "Hey Siri, butter my toast." "Bought you a helicopter and a standing ovation." "A Jedi Knight in dungarees." This quote came from her video, Hereʼs to Laughing (her tics are in parentheses): "Adults are often nervous about even calling me disabled. They clearly see it as a negative term. I donʼt see it that way at all. Saying Iʼm disabled acknowledges the barriers I face because of a collective failure to consider difference (biscuit). Pretending these barrier donʼt exist doesnʼt make them go away (biscuit)...As soon as we stop shying away from difference, we can start appreciating our similarities (hedgehogs, cats, biscuits)."  Jess shared five ideas to help shape the future of young people because being inclusive doesnʼt have to be difficult:

Their last two points really resonated with me: find ways to stay connected even when the program is over and help them enter this world by showing them how. In many ways, this young man addressed the importance of social and cultural capital, which Alastair Wilson and Katie Hunter at the University of Strathclyde have tried to address with their Intergenerational Mentoring Network, which supports one-to-one mentoring to improve outcomes for youth as they progress through the education system. The network draws on the knowledge, experience and networks of older adults and retirees to help students successfully access careers in which theyʼre interested. I also had a chance to network with many professionals interested in the intersection between music education, inclusion and social justice. Katy Robinson from the National Foundation for Youth Music shared this Reports and Resource page, which includes Youth Music evaluation tools and a quality framework.  And last but not least, I met Fran Hannan, Managing Director of Musical Futures (MF). She is one of the main reasons why I am here in the UK. The work that she has done in the field of making music accessible to all students is inspiring. I am excited to take Musical Futuresʼ trainings that she and her Champion MF teachers will be offering throughout my tenure here. She also has connected me to schools throughout the UK that are implementing Musical Futures approaches in their music class. Thank you, Fran, for your generous spirit! I look forward to March when Iʼll be attending your Just Play training in Carlisle. On my way back from the Winter Fiddle Festival in Kelso, I planned a stop in Edinburgh to visit my friend and fellow Fulbrighter, Shana Ferguson. The train ride is under an hour and I had the good fortune of sitting next to Alasdair Fraser who was also making his way to Edinburgh. During the the trip, he was kind enough to share his thoughts on traditional music and teaching. Alasdair started our conversation by saying that the phrase, "Learn by heart" means just that: music comes from within, not from a sheet of paper. Thatʼs why his teaching style focuses on "undoing" and "unpacking" so that students can look within for their music and have the space in which to do it. Alasdair questioned why we equate music to notes on a staff when music is an aural medium. Each flourish can be played differently each time you play the tune (i.e. how you enter into the note, how long you stay on each note, etc.) Those kinds of decisions come from within and canʼt be constrained by visual representation on sheet music. Alasdair shared that his passion for traditional music comes from a place of anger - a fire in his belly. His grandfather couldnʼt speak Gaelic because it was seen as the language of poverty and the poor so schools wouldnʼt allow it. Alasdair didnʼt go to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland because students would be kicked out if they played Scottish music. He has seen how many organizations come from a position of power and injustice. It is one reason why Alasdairʼs fiddle program is non-institutional and involves no money. It is founded on 4 key principles, which creates a safe place to be who you are:

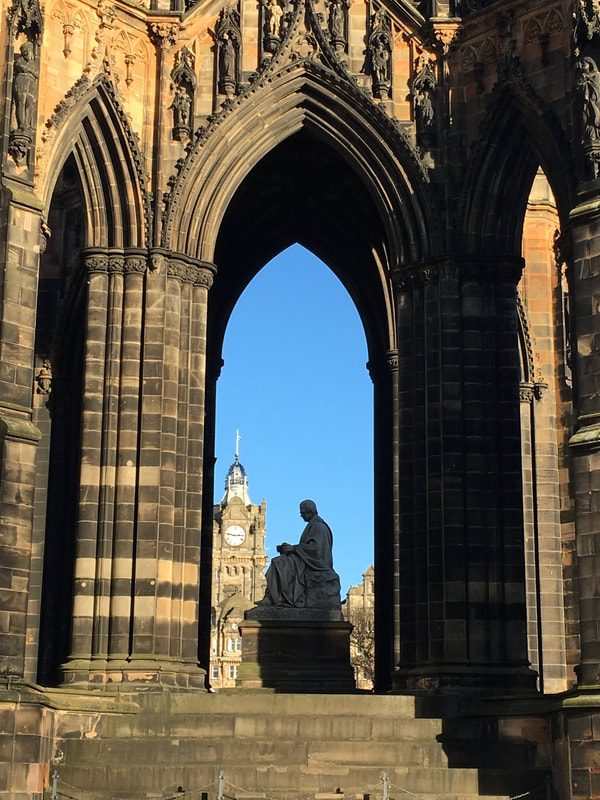

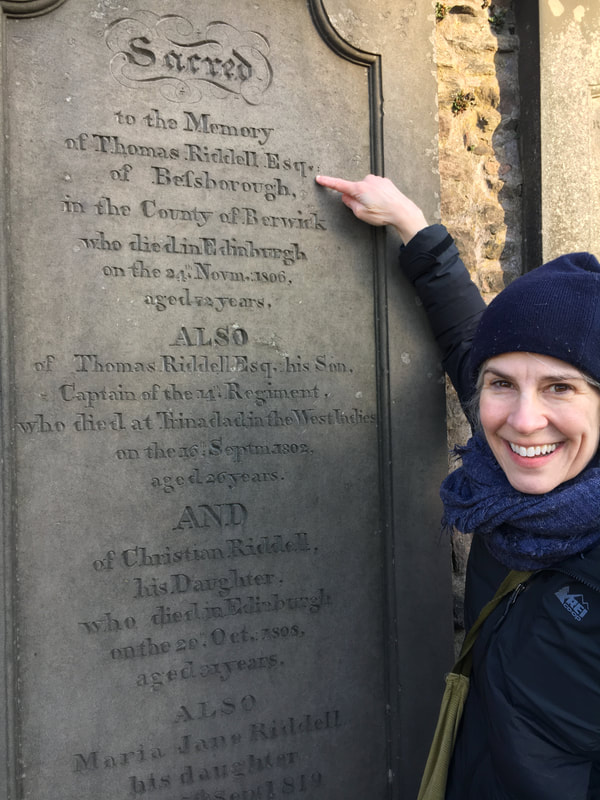

My time was short in Edinburgh, but Shana was kind enough to take me to the cemetery where Thomas Riddell of Harry Potter fame is buried. We made it just in time as a tour group of Harry Potter fans were on our heals. Thank you, Shana. You helped me find the right angle for my shots. I look forward to seeing you again in March to hear your presentation at the University of Edinburgh. I also stopped in a nearby cafe for an oatmeal latte and chocolate chip scone with cream and jam. When my server found out I was from Alaska, she could hardly contain herself. It has been a dream of hers to travel there someday. I gave her an Alaskan pin to help keep those dreams alive :) As a classically-trained pianist, I learned at an early age that you play whatʼs on the page and donʼt deviate. And even though Iʼm a confident sight-reader, playing by ear and improvising terrify me. I donʼt want my students to have the same experience. They deserve to navigate freely between both worlds to become a more well-rounded and skilled musician. Thus the reason for jumping on a train and then bus to the beautiful border town of Kelso, Scotland to dive in to the world of traditional music at the Winter Fiddle Festival, sponsored by the Merlin Academy of Traditional Music. And yes, playing by ear! I love the concept of these festivals or fèis (immersive teaching courses, specializing in traditional music and culture) because people gather for an intensive period of time to learn new tunes during the day and play together in a session (a social gathering where folks perform in an informal setting - i.e. pub) at night. I arrived in Kelso Friday afternoon and walked around town taking in the sites, including 12th century Kelso Abbey (photo below left) and North Parish Church (photo below right).  What made this weekend even more thrilling is that I met Iain Fraser, the Director of Merlin Academy, who led many of the sessions. Ian developed the Glasgow Fiddle Workshop (where I take fiddle and mandolin lessons), has been actively involved in Fèis Rois, and was the principal fiddle teacher in the Scottish Music Department of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. He also edited Scottish Fiddle Tunes: 60 Traditional Pieces for Violin, which is the music book I had been using back in Juneau, Alaska to help prepare me for my trip to Scotland. Iain has been key to promoting and sustaining traditional music in so many ways throughout Scotland, yet this inspiring teacher is very unassuming. For me, it was like taking a photo with a rock star! The experience of learning to play a tune by ear at a fèis was humbling. As others picked up the tune quicky, I found myself desperately trying to create a mental image of the sheet music in my mind. It slowed me up considerably, but my mind was clinging to old habits. At the evening session, I was way out of my league trying to play along with folks, but everyone was encouraging. "Just pick out a few notes and play those. It gets easier the more you try." Graeham, one of our instructors said, "Play what works for you. Mistakes can often lead to improving the song. Tradition isnʼt something thatʼs fixed. It moves, it lives - itʼs totally grand!" And David, a fellow participant, (photo below) shared, "Traditional music is molded by the people who play it." There was an encouraging, non-judgmental and inclusive feel to the entire weekend: young peopled performing with adults and beginners playing alongside advanced fiddlers.  At one point, when the music was just too advanced for me, I asked the father of one of the young fiddlers how to play the bodhran - an Irish framed drum. Since I played snare in the City of Juneau Pipe Band, I thought Iʼd have better luck. He was a great teacher and told me to remember that most of the rhythms can be played by thinking "Watermelon." And he was right!As we moved into Sunday, I was identifying more of the patterns and hearing the relationships between notes and phrases. The whole of the group played with more joy, musicality and connection to one another without music in front of them. This became even more evident when we were given music for one tune by a visiting musician. All of a sudden, heads were buried in the music. Yes, I felt like I could finally hang with the big wigs and shout out, "See, I can play!" but I could hear the difference in the groupʼs sound. We were disjointed, more mechanical and no longer focused on one another, but on a single piece of paper. We looked more serious than joyful. It reminded me of Davidʼs story.  Davidʼs Story: David plays the fiddle and learned traditionally by ear. He shared that his granddaughter was banned from school orchestra because she couldnʼt read music, yet played at an advanced level. David said it was fèisean like these where his granddaughter discovered that she wasnʼt alone and that another world existed where she could "play like her grandpa." She has since been invited back to her school orchestra. David said sheʼs learned how to navigate both worlds, but sadly has learned not to mention grandpa in school. I know this heartbreaking story has been told by others on both side of the Atlantic. I wonʼt forget this story, David. Thank you for telling it and allowing me to share it.  The videos below are just snapshots of this inspiring weekend. This first is a tune led by Iain Frasier and his brother, Alasdair. The second is one of the evening sessions with folks gathered in the common space of the hotel. Many thanks to Director, Bridget Gray (photo to the right), for creating a community music program for all ages to experience the joys of making-music together. Click here for more photos and videos of the Winter Fiddle Festival. And for more information on the incredible work of the Merlin Academy of Traditional Music, including their weekly lessons and summer camp in August 2019, check out their website. The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland (RCS) has a Traditional Music program and Josh Dickson, an Alaskan, heads the department. I had the pleasure of meeting Josh at the Conservatoire and appreciate the time he took to talk with me about the Traditional Music program and how he came to live in Scotland. Josh grew up in Anchorage and learned to play the Scottish pipes in a local pipe band in which his father played. In 1992 Josh traveled to Scotland where he received a MA in Scottish Gaelic at the University of Aberdeen and completed his doctoral studies in the history of the piping tradition of the southern Outer Hebrides at the University of Edinburgh. The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland is the only university in the UK, which offers a Bachelor of Music degree dedicated to traditional and folk music in these principal studies:

Because Scottish music is traditionally taught by ear, students applying for this program do not need to know how to read music to be considered for entry, but once they are a student at RCS they do learn to read music as an equal skill to ear-learning. read music. Over the course of this four-year degree program, students also take courses in music theory, arrangement, composition, research skills and teaching in a range of environments. Josh likened the approach of the traditional music program to the term, "Dig Where You Stand" which is the idea of understanding self first by unpacking who your are and from where you came before branching out to the wider world. Josh admits that this approach counters those of most university programs, which start broadly and then progress to more focused and specialized coursework, but feels it better aligns and supports students entering this discipline. We talked about the parallels between Gaelic and Native Alaskan music: both taught by ear and considered an integral part of daily life. Josh shared the tradition of the Waulking Song, which are Scottish folks song traditionally sung in Gaelic by women cleaning the cloth to make it fuller (waulking). As a group, the women improvised a song while rhythmically beating the cloth to soften it. Josh invited me to the Conservatoireʼs Friday afternoon Sang Scuil/Sgoil nan Oran, which is Scots and Gaelic for "Song School." There students sing traditional songs from many cultures. I shared a song in Tlingit to give them an opportunity to hear and sing this beautiful language. Thank you, Josh, Corrina Hewat, and all of the singers for welcoming me. I look forward to hearing you perform this spring.

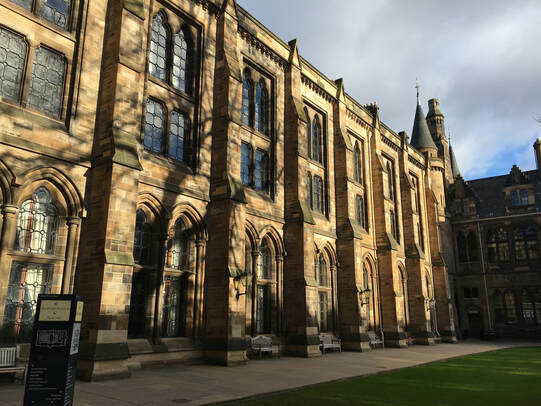

In an earlier post, I shared experiences of why People Make Glasgow and am reminded of this cityʼs theme on a daily basis. Whether a stranger stranger striking up a friendly conversation while in the grocery line or a passenger on the bus helping me understand how to purchase bus tickets, every person with whom Iʼve come in contact has a generous and friendly spirit, which is quite uncommon for a city this size (1.2 million or the most densely populated city in Scotland). The location of the mural in the photo above has great significance to the people of Glasgow. According to this article in Glasgow Live, the mural "looms over the much-loved Clutha pub, where 10 people tragically lost their lives when a police helicopter crashed into the roof in November 2013. The mural not only hails one of the city's greatest legends, but will serve as a constant reminder of Glasgow's community spirit – one which can never be dampened even in the darkest of hours." Yes. The arts play a vital role in the well-being of this cityʼs residents. I was thrilled to share Glasgow with my Fulbright colleagues and friends, Keith Thompson and Shana Ferguson, during Robbie Burns weekend. Robbie Burns was born January 25, 1759 and is considered the national poet of Scotland. Burns wrote in the Scots language before it was popular to do so in literary circles and helped preserve hundreds of Scottish folk tunes and lyrics handed down aurally over the centuries by collecting and recording them. He also was a prolific songwriter and adapted the words of old Scottish folk songs. Although he is often attributed to writing Auld Lang Syne, he collected the songʼs first verse, adapted it and then wrote the remaining three. Burns Night is treated much like a national day where Burns poems are recited, his songs sung and his famous poem, "Address to a Haggis" is recited before the ceremonial haggis is cut. Shana had found a most fitting location to celebrate Burnsʼ Night: Britannia Panopticon, the worldʼs oldest surviving Music Hall! I had taken a tour of this hidden gem earlier in the week as part of Celtic Connections. Opened in 1859, the Panopticon hosted some of the biggest names on the music hall circuit, including Stan Laurel, who made his first stage appearance there as part of an amateur night in 1906. Robbie Burns Night festivities reflected the spirit of this hall with music, song, comedy and the traditional end of the night singing Auld Lang Syne. On Sunday we toured The Hunterian on the University of Glasgow campus before treating ourselves to Afternoon Tea at the Willow Tea Rooms, inspired by the works of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, who sadly died penniless in 1928. Our weekend ended with this chance encounter of the Street Orchestra Live performing outside Glasgow Royal Concert Hall. According to their website, their mission is to "take orchestral music to everyone, anywhere" by giving free performances in public spaces and "is committed to providing concerts for communities with little or no opportunity to hear live music." Check them out on Facebook. “If the primary aim of music education is to help foster creation of the student’s self-identity, then informal learning is not only a good way to learn, it is the ideal way to learn” (Jenkins, 2011, pp. 194-5). As a music teacher and director of an El Sistema-inspired program focused on student empowerment, leadership and citizenship through music ensemble, this quote from Jenkins (2011) sparked my curiosity. If informal learning plays an invaluable role in a child’s education, why is this type of learning often absent from the school classroom? Can a school music classroom include informal learning as part of its learning environment? As part of my Fulbright research, I am exploring the concept of informal learning through many different pathways. One of these paths has been through Dr. Theriaultʼs Informal Education course at the University of Strathclyde. According to Dr. Theriault there are three different approaches to education:

With the impact of the internet and social media on studentsʼ lives, informal learning aligns well with the environment of todayʼs learner and can be a solution for meaningful change within learning institutions. According to Beckett and Hager (as cited in Jenkins, 2011) information learning has six key features: organic/holistic, contextual, activity- and experienced-based, arises when learning is not the main aim, activated by individual learners (not by teachers), and often collaborative. Lucy Greenʼs (2005) informal learning pedagogy is one of the reasons why I hoped to earn a Fulbright scholarship to study in the United Kingdom because this informal approach provides classically trained instrumental and classroom music teachers (i.e. me) with practical tools to successfully integrate informal practices of popular musicians into their teaching. According to Green (2013), “Informal approaches tend to involve a particularly deep integration of listening, performing, improvising, and composing throughout the learning process” (p. viii). Musical Futures was founded on Green’s model, which encourages student-driven learning, collaboration, and group performance. Through self-teaching and providing a relevant social context, Musical Futures helps students develop their musical identity and gives them an equal voice in the classroom (Wright, 2014). This March I will have the opportunity to take Musical Futuresʼ trainings and observe programming at Musical Futures Champion Schools throughout England.  In closing I want to thank Dr. Theriault for her friendship. She has met with me on a weekly basis and put me in touch with university staff and community members who could support me in my research. References

Green, L. (2013). Hear, listen, play!: How to free your studentsʼ aural improvisation, and performance skills. Oxford: University Press. Green, L. (2005). The music curriculum as lived experience: Children's “natural” music-learning processes. Music Educators Journal, 91(4), 27-32. Jenkins, P. (2011). Formal and informal music educational practices. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 19(2), 179-197. Wright, R. (2014). The Fourth Sociology and Music Education: Towards a Sociology of Integration. Action, Criticism & Theory for Music Education, 13(1.) |

Lorrie HeagyThis is a personal blog, sharing my experiences living in the UK from January - June 2019 as a Fulbright Distinguished Award in Teaching scholar. This blog is not an official site of the Fulbright Program or the U.S. Department of State. The views expressed on this site are entirely my own and do not represent the views of the Fulbright Program, the U.S. Department of State, or any of its partner organizations. Archives

July 2019

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed